Lionel George Henricus Wendt was born on December 3, 1900 in Colombo, Ceylon. Musician, photographer, literature collector and aficionado of the arts, Lionel Wendt pioneered a new artistic vision for Ceylon.

The pianist, photographer, critic, and cinematographer Lionel Wendt was the central figure of a cultural life torn between the death rattles of the Empire and a human appraisal of the untapped values of Ceylon.

Pablo Neruda, Memoirs

His father, Henry Lorenz Wendt, a burgher, is a judge of the Supreme Court and a legislative adviser. He is also one of the founders of the Amateur Photographic Society of Ceylon (1906). His mother, Amelia de Saram, is Singhalese. Daughter of a district judge, she is an active social worker, organizing numerous concerts for charities.

Lionel was regularly taken by his father to A.W. Andree’s Hopetoun Studio, where he was ‘particularly intrigued by a large camera on castors with a musical box attached to it for the amusement of children’. His only recreation, wrote Andree’s son, ‘was a small box camera which my father gave him. In my father’s studio he “learned” the fundamentals of an art he was later to revolutionize.’

His father died, very suddenly, before Lionel was eleven and his mother less than seven years later. Despite the early dedication to music, family traditions and prevailing attitudes would not permit a purely musical career.

He went to London in 1919 to study law at the Inner Temple. His younger brother Harry followed a few years later to read the same subject at Cambridge. London gave Wendt the opportunity of advanced training at the Royal Academy of Music under Oscar Beringer, in the master classes of the famous pianist Mark Hambourg, and with Hambourg’s pupil, Gerald Moore.

Had he been solely determined upon a career as a concert pianist, he might have remained in Europe after the completion of his legal studies. The decision to return in 1924 not only marked the commencement of his adult professional life but also suggests a commitment to his country and an eagerness to intervene in its society, art and culture.

Scarcely practising as a lawyer, however, though enrolled as an Advocate of the Supreme Court of Ceylon, he soon began to give public recitals, both as soloist and accompanist. His interest in the modern movement is manifest in his earliest concerts, where he introduces works, which had rarely or never been performed here.

He wasted no time in giving public piano recitals, both as soloist and accompanist. He abandoned the law for music in 1928 and developed an interest in avant-garde music.

Lionel Wendt became the figurehead of the only circle of avant-garde artists of the time, which included, among its members, his childhood friend, the painter George Keyt. In his autobiography, the poet Pablo Neruda, Chile’s consul to Colombo in 1928-1929, writes:

I realized that Lionel Wendt was the center of cultural life, which struggled between the groans of the empire and an attraction for the virgin values of Ceylon. Lionel Wendt, who owned a large library and received all the news from England, took the extravagant and good habit of sending a cyclist loaded with a bag of books to my home, which lived far from the city.

Lionel Wendt and his friends were trying to contribute to the formation of a modern national awareness. They deeply felt that the future of the country could not be built by ignoring an ancient heritage or rejecting the Western way of life, but rather a fusion of the two.

At the beginning of the 1930s, while continuing to give piano recitals, Lionel Wendt turned to what became his great passion, photography. It is said that it is in photography that Wendt finds the ideal vector to promote the values and way of life of the inhabitants of Ceylon.

L. Wendt at the piano, by Geoffrey Beling

In January 1930, supported by Winzer, Wendt organized what can now be seen as a landmark exhibition of work by Keyt and Beling. It drew a lyrical review from Pablo Neruda – translated by Wendt from Spanish – where he described the painters as being ‘orientated directly toward the Future, which is the Polar Land, the inevitable country of exploration for all true artists.‘

Even establishment figure, physician and antiquarian, Andreas Nell, while admitting to a sense of ‘unhappiness’ and dissatisfaction, praised the young painters for ‘forsaking the local godlings of imitation and reproduction, and seeking instead to interpret and create.’ Reflecting dominant opinion in the Society of Arts, however, Mudaliyar Amaraseka, virtually called the exhibits ‘ridiculous and degrading,’ and those who admired them, ‘imposters’ or ‘degenerates’. Another writer mocked Wendt, calling him a ‘modern Moses leading the elect out of the land of the Philistines’ to the ‘promised land of Cubist, post Impressionist and Futurist Art’ – all of which provoked only amused rejoinders from Wendt himself.

Winzer had anticipated such reactions, remarking in a foreword to the catalogue that any young artist who ‘turned for advice and inspiration to the works of modern masters’ was proclaimed as being “morbid” or “not original”, an “imitator”, a “cubist”, a “modernist” – for to belong to our own time, to try and discover new modes of expression or execution is considered a departure from good taste.’ In February, Wendt published a thoughtful appraisal of Otto Scheinhammer’s farewell exhibition. This, too, provoked a skirmish in the press.

The camera becomes a living thing

A cryptic dedication in Wendt’s 1940 exhibition catalogue credits his brother Harry with being ‘responsible for the relapse which turned a childhood hobby into a major preoccupation’. This seems to have been around the beginning of the 1930s – first with small Rolleiflex and later with the miniature Leica. By 1933 he was developing and printing his own work.

In 1934, with photographer friends, Wendt revived the Amateur Photographic Society of Ceylon founded by his father and renamed then Photographic Society of Ceylon, still active today. He participated in many exhibitions in Ceylon between 1935 and 1944. His photographs were also exhibited in Europe, in particular during a personal exhibition sponsored by the Leica company at the Camera Club of London in 1938.

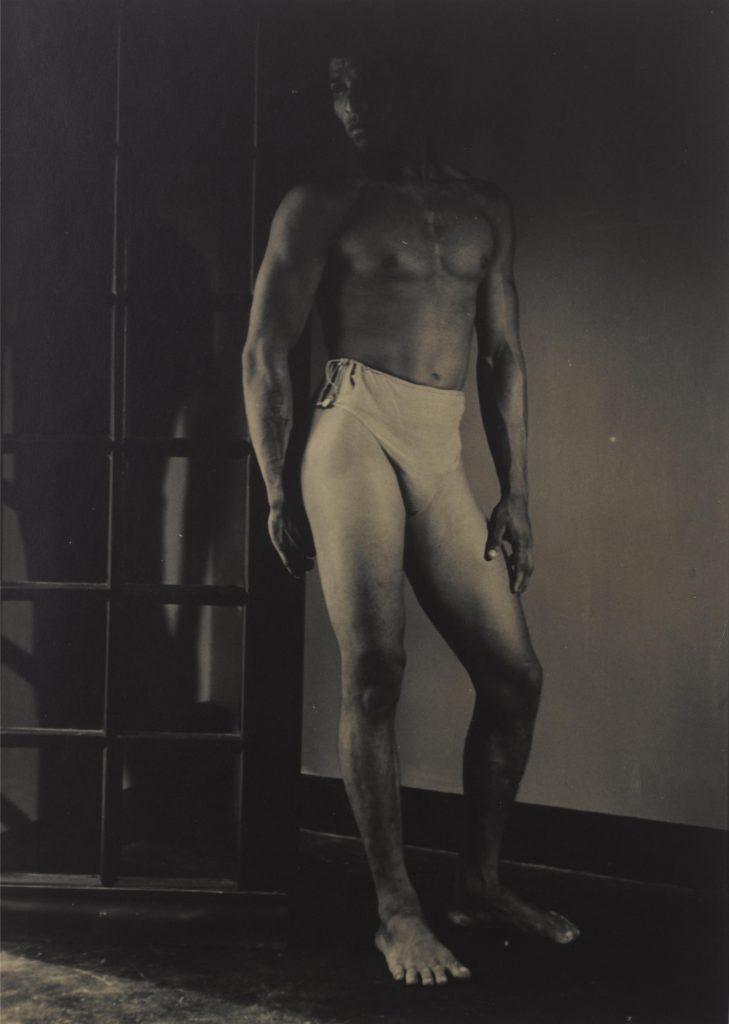

Wendt testifies with his photographs of the culture of his country. The male body was his favorite theme. He also addresses landscapes, daily life, architecture, archeology. He reconciles knowledge and interest in modern artistic trends (Magritte, Man Ray, Chirico) with a concern to represent traditional Ceylonese life. His fertile imagination calls upon a multitude of techniques: photomontage, photo collage, solarization, relief printing, photogram.

Lankatilaka Dagoba

Architecture surréaliste

Beach landscape

Boat dock, cat

Buddha head and wine goblet

Sea landscape

Untitled (Buddha head among branches) 1939

Untitled (still life with mask and statue) 1942

In 1934, British director Basil Wright associated Wendt with the production of his documentary Song of Ceylon. Described by Wright as one of the six best photographers in the world, Wendt is not only the narrator of the film; his photographer’s eye and his in-depth knowledge of the country and its culture are an essential contribution to this documentary considered major.

Without him, I doubt Song of Ceylon could have been what it is. Because Wendt had a deep knowledge of Ceylon, he was in contact with avant-garde cinema of the time and he knew the world of documentaries. In fact, the only two people I met in Ceylon who knew anything about cinema were Wendt and artist George Keyt.

Basil Wright – In an interview published in 1949 in Mosquito

The magazine for Ceylonese students in England

The collaboration between Wendt and Wright will continue after the filming of Song of Ceylon, the photographer staying several times in London to become Wright’s assistant in the company he had founded. Wendt was the first Ceylonese to establish a relationship between photography and cinema when the latter developed on the island during the 1930s.

Lionel Wendt and George Keyt play a leading role in promoting Kandyan dance. They behave like real patrons of dancers and drummers from around Kandy: Suramba and his brother Jayana from the village of Anumugama, Ukkawa and his brother Gunaya from Nittawela. These artists will be among the most talented and well-known representatives of Kandyan dance.

Nittawela Gunaya

Lionel Wendt’s contribution to the development of modern painting in Sri Lanka cannot be emphasized enough. Subscribed to numerous art and literature reviews such as The Studio, Cahiers d’art, Minotaure and Transition, Wendt is the extremely devoted protector of a group of painters. He buys some of their works, organizes exhibitions, and publicly defends these painters in the newspapers.

A climax in Wendt’s artistic life came with the formation of the 1943 Group, that loose association of independent painters which is now considered to be one of the most important mid-century expressions of modernism in Asian art. The initiative to form the group appears to have been taken by the young and energetic Ivan Peries, but it required the personality and stature of Lionel Wendt to be the central figure, presiding over the varied and conflicting temperaments of the artists involved, several of whom were his close personal friends.

The group’s inaugural meeting is held at his home. It involves bringing together independent artists, such as George Keyt and Ivan Peries, who are today recognized as among the best representatives in Asia of mid-20th century modernism.

The 43 Group, by Aubrey Collette.

From left to right: Geoffrey Beling, Harry Pieris, Richard Gabriel, Ivan Peries, George Keyt, Lionel Wendt (seated), George Claessen, Aubrey Collette, Justin Daraniyagala, Manjusri Thero.

Lionel Wendt’s sudden and untimely death in December 1944 came as a heavy blow to many, but most of all to his brother Harry, whose own death followed a year later. Before Harry died, however, the Lionel Wendt Memorial Fund for the promotion of the arts, was established. Its contributors desired to perpetuate ‘the memory of Lionel Wendt’s lifelong devotion and valuable services to music and the other arts in Ceylon, and the high place he occupied in the esteem of all who knew him, particularly students and lovers of the arts.’ Except for some personal bequests, the entire property and assets of the two brothers seem to have passed directly or indirectly to this fund – after Harry Wendt’s death, through the intervention of their friend and chief trustee of the Lionel Wendt Memorial Trust, Harold Peiris.

Before Harry Wendt’s death, a decision had been made to bring out three volumes of Lionel Wendt’s photographs. One volume of 120 plates was finally published in 1950. It is a beautiful book, idyllic, celebratory, and almost all there is to tell us of his work, of the sensitive eye and the creative imagination. But one misses certain elements – the photographic series (like Metamorphosis or Northern Journey published by Wendt in the Ceylon Observer Pictorial), Wendt’s own titling of certain pictures, some chronological data and, above all, the famous self-portrait (frontispiece) – which appeared only on the flap of the dust-jacket.

This publication showcases a selection of Wendt’s photographic works taken in Ceylon. The works are divided in the following sections: Landscapes, Types, Nudes, Details, Buildings and Ornaments, Fantasy, and Heads.

Includes an introduction by L.C. Van Geyzel which provides insight into the life of the artist. Bernard G. Thornley contributes notes on technical details of Wendt’s photographic practice.

‘Alborada’, the house he built and lived in from the late twenties, was demolished in 1950 to make way for the first stage of the Memorial complex. The Memorial Theatre was opened in 1953, and the Lionel Wendt Memorial Art Gallery in May 1959, both based on designs by Geoffrey Beling. The Photographic Society held an exhibition of its work to coincide with the gallery’s opening. A display and sale of Wendt’s photographs were included but they were not listed in the catalogue. This seems to have been the last public exhibition of his work until 1994.

Lionel Wendt was famous at his death, and frequently referred to as Sri Lanka’s foremost camera-artist. It is regrettable that a fellow-photographer destroyed all his negatives after Wendt died, on the basis that this was an accepted practice in photographic circles. If it were not for the single volume of 120 plates, published 46 years ago and long since out of print, Wendt’s photographic reputation and contribution would have receded into the obscurity

In 1967, the Lionel Wendt Art Collection was put up for auction. About 20 pictures were bought by the Trust’s Chairman Anton Wickremasinghe, who said that he intended ‘to make them the nucleus of a collection to be later made available to the public’. On his death in 1993, however, they found their way into new private ownership.

The rediscovery of Lionel Wendt is dependent on the preservation and publication of his extant photographs. It implies not only a consideration of his contribution to Sri Lankan art and culture in the twentieth century, but also an estimation of his place in international photographic history. How much weight would we give today to the assessment made five years after Wendt’s death by the director of Song of Ceylon, Basil Wright:

I think he was one of the greatest still photographers that ever lived. I should place him among the six best I’ve come across.

Credit – Suravi France, Ellen Dissanayake, Asia Art Archive, Travel Film Archive, ThreeBlindMen Photography

Loading…

Loading…